HOME > Departments and Programs > British sound artist Dr. John Richards gave a lecture and workshop at the School of Design and the Graduate School of Design.

School of Design

KamataBritish sound artist Dr. John Richards gave a lecture and workshop at the School of Design and the Graduate School of Design.

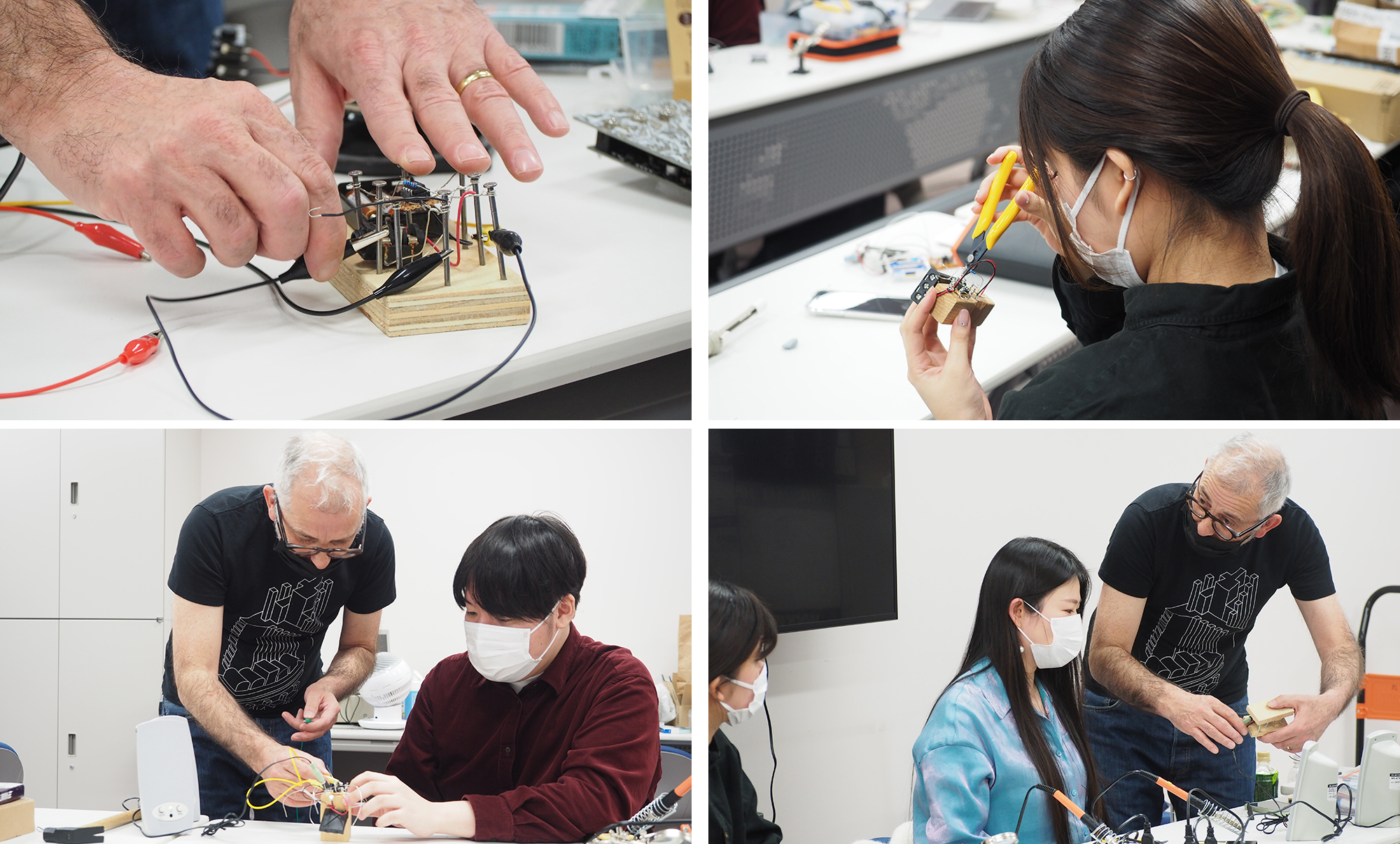

In December 2022, the School of Design hosted a lecture and workshop by British sound artist Dr. John Richards. On December 13, 3rd-grade faculty students in the "Sound Design Skill" class received a lecture for learning the principle of electronic sound. On December 16, 1st-year graduate students in the class "Digital Design Skills II" participated in the workshop to make simple synthesizers. Both classes are organized by Prof. Seiichiro Matsumura, School of Design and Graduate School of Design.

The following interview was conducted after the December 16 workshop. Dr. Richards talked about a wide range of topics, including artistic expression, design, research and education which provided a variety of insights for our university education.

John Richards (Dirty Electronics): https://www.dirtyelectronics.org/

I (Interviewer): Could you explain your artwork or your activities?

J (Dr. John Richards): Well, I am best known for my work as Dirty Electronics, which is about getting your hands dirty, working with sound-making circuits. So, they can consist of wires or electronic components but I also make digital synths, as well as work with microprocessors. And I like to explore how making stuff and sound coexist in some interesting relationships. I also like making electronic sounds with lots of people, so it's not about the solo, bedroom artist but making stuff, finding how to play this stuff and then playing together with other people. This is something that I really enjoy. And when I make sound-making synths or objects, this creates the opportunity to either play together with others or to find new things for the first time. If we all make something from the beginning, from scratch as we say, we’ll have the same starting point. So, today we made this sound-making circuit and perhaps you or I don't know how to use it yet, but it was the same for everyone who we worked with today. We all began kind of at the same place, from a "tabula rasa", Latin for a "clean slate", which is kind of very important creatively. A clean slate gives you the freedom to build something, to find new music. That is one of my motivations for approaching electronic sound and art in this way and not to rely on proprietary software or hardware.

I: So, you are expecting to trigger such reactions from people?

J: I feel that collective design is interesting. There are a few different approaches here. There’s the sound, there’s the music, there’s the performance, there’s design and I think my work covers all of these things. Sometimes you look at it, and it’s really about exploring critical design, how we prototype or think about a new musical instrument, or how we might interact with something.

There is an element of interaction design in the work but the interaction design can also overlap with how we might approach the performance or music. These are the things that I'm interested in exploring: interaction design, sound making, and performance. But ultimately, you have this collaborative approach. So today, for example, I had a blueprint or structure but through working together we explored different possibilities and each person taking part came up with different possibilities. I won't say solutions. That seems too precise but so many ideas, new ideas, were brought to the table by different participants. I’ve done this particular workshop many times in different countries all around the world but each time somebody comes up with a different approach, a slightly different way of doing things. And over the years through that collective workshopping or activity, I’ve also learnt new ideas about design. So, this kind of collaborative making is a bit like rapid prototyping or a way of thinking of design but using collaborative approaches.

I actually also like approaching music in the same way. That involves people coming together. We sometimes call it devising, you know, you don't compose the piece and tell everybody to play it. You come to the rehearsal space with a few ideas, a blueprint and then create the work collectively. It’s a kind of way of using everybody's expertise. I like to work, and debate, and discuss, and collaborate in terms of creating music as well. So, my approach to music-making is similar as it is to design. You have a discussion. It's two-way, three-way, multiple-way discussion. Maybe this creates an issue of who is the author, who is the designer because everybody contributes. This can become a little problematic. Yet, most of my artwork in that sense is collaborative.

I: So, you mean your artwork or activities such as workshops are a kind of platform for collaboration or discovering design ideas which are buried in each participant.

J: Exactly. In more recent times I've tried to avoid the term ‘workshop’ or this idea of the ‘tutor’, because then I become the teacher of the group. But as you saw today, I created the platform but everybody else came with ideas, and then this makes a more interesting environment to collaborate. So, I have to respect the participants. But really they are no longer the participant. They become the collaborator. There's a shift. I've shifted from the idea of working with participants to thinking about everyone as potential collaborator and I think the results are better. Then the conversation continues. I might go to China and do a piece or event like this or go to a place in the UK or Germany and then somebody will write to me two years later, one year later maybe. I even work with them in the future sometimes. The workshops also become good places to meet people, like-minded people. You’ll see my outputs and be able to trace back where I might have met one of these people, often like the activity we did this morning, and you continue to have a relationship.

I: In that meaning, you are sowing seeds?

J: Yes, you could think of it as sowing seeds, creating a platform, creating a dating agency for noise!

I: Okay. That's nice. So, the second question. Could you tell me about your career, working or education career?

J: Yes, I almost went to art college. But I had, as we say, my head in the clouds. I was a bit of a dreamer and I liked playing the piano, and when I became a teenager that's all I did. I played the guitar a bit too. My parents were very unhappy about this because they wanted me to go to college or university. And my next-door neighbour ran a guitar workshop where he made guitars and I announced to my parents that I wasn't going to university. I was going to make guitars with my neighbour, which also didn’t go down very well but it was a great thing. The guitar maker was also, in his previous life, a drama teacher. He was very good at teaching. I also had music lessons and he let me have Wednesday afternoons off to go to piano lessons. I was totally obsessed at this point with music. He said to me there’s this really interesting college for contemporary art, perhaps you should go there and it was called Dartington College of Arts. Historically, this college is very important. Many great composers have visited Dartington like Stravinsky and John Cage. It is a very important place in history not only for music but also for visual arts and dance, and many other things. I got a place and I went to this art college. It radicalized me because there was so much contemporary music and so much contemporary art. As a young person, I loved it. From then on, I just carried on in the same spirit enjoying, experimenting, playing with materials, and playing with people, exploring different art forms. I remain hungry for the arts. From that moment, my life changed and maybe the guitar maker also changed my life. I’ve lost contact with him over the years, but recently I tried to find him again, to write to him and thank him for the inspiration and opportunities he gave me. He was a big influence on my life at that time.

Anyway, from then I carried on studying and playing and I went to York University in the north of England, did a PhD in electronic music, and carried on and on, and did more and more. York was very good because I started thinking a little bit more carefully about what I was doing. The professors there helped me articulate some of my thoughts and develop my practice. York University was very good because this idea of practice and theory coming together was seen as vital, very important, not just musicology or academic work, but practice. Practical things could also be seen as critical in what we consider as research. So, York helped me in that sense to start also writing about some ideas in a clear kind of style. I also started writing a little bit about some of my practice and contemporary music and electronic music.

So yes, I have a career of teaching, performing and writing but I see it all as the same articulation of an idea or a practice. It is very important to me to actually do things, to make things still. It's very easy as you get more senior to become distant from the material or the practice. So, I have to keep practising, keep making, keep playing, keep making sound. This is a very important motivation I still have, to hold on to that. And during my study, this was ingrained in me that you combined theory and practice. Well, you could say in general that this is a very British approach to academia where practice and theory are combined. So, in my case, that meant playing an instrument as well as thinking about music and musicology at the same time, which is very different, for example, from going to a music conservatoire where you might just study playing an instrument. When I was at York, I did an exchange with a university in Berlin and studied musicology. There, musicology was seen as something separate from playing, for example, the piano or an instrument. The conservatoire was for studying your instrument and the university was for musicology.

This wasn't the case for me. I was brought up having to think about both. Sometimes it can be difficult because you're having to do many things. Maybe it's like being a Renaissance person again, where you combine different skills and there is an open approach to combining different things. I mean, Leonardo da Vinci, for example, was a painter and a designer. He had many attributes that he combined. And I think in my practice - even though we are told to specialize, specialize, specialize, focus, focus, focus - I love combining the different parts of me, or my interests. Then it feels like something whole. Maybe there’s a little bit of Zen philosophy in there, thinking about it all as a whole. Although I’m not a particular religious person.

I say it’s a little bit like a garden when you neglect parts of the garden and things get a little bit tired or they die, which isn’t very good. So, you’ve got to try and maintain all the garden for the garden to be healthy and not leave bits of the garden without water. When I'm happiest – which I think is an important part of art-making, I want to be happy, why would I spend my time making art and being unhappy – is when all of the garden is watered and being looked after.

I: What kind of impression do you have during the workshop or the lecture at this University?

J: It's always very exciting coming to a different country and different culture and, like many of the workshops I give, being surrounded by a new generation of up-and-coming artists, and here there are many young vibrant exciting people who I think will be the future. Yeah, that's the most exciting thing about coming to a place like this. And, maybe, not yet knowing what they will do in the future. So, this is an institution that embraces different technologies and different approaches to the arts without being particularly dogmatic. In the world of art, we have different disciplines such as a fine art or sculptor or music. But here it feels a bit more open in that regard. So, I think this institution challenges disciplines in a way which makes us think about what an art discipline could be in the twenty-first century. I really like that about meeting the students here, where the idea of discipline is open and still being explored. I don't feel it’s the same, for example, when I do a workshop at a music conservatoire. It's a different feeling, sometimes not so good. In such an institution, we might say the students have too much baggage. For example, they're already ‘the’ musician.

I: They're fixed?

J: Yeah, they’re already on a set path. Maybe there’s an advantage here in that you are a university of technology. Technology doesn't dictate a discipline per se. This leaves the idea of discipline open in a way. That is something to be celebrated.

I: So, you see some possibilities here for the students?

J: Yes, there is a kind of discourse relating to disciplines. But it is interesting how technology has impacted on the arts and disciplines have dissolved or evolved. So, for example, traditional materials and their use in fine art, such as acrylic or oil paint, may help define a discipline. But in our workshop today, what materials as such define our discipline? A microchip or the wire that we used? It's quite interesting to think about our point of connection. This point of connection might be technological rather than a particular approach to making art or sound. So, that also feels very new. And on the one hand, it's exciting but on the other, a little bit frightening. But we remain discipline-free.

Interview and translation:School of Design Seiichiro Matsumura

https://www.teu.ac.jp/gakubu/design/index.html